Tapeworms found in man’s brain years after he ate feces-tainted food - Ars Technica

On a night that seemed like any other, a perfectly healthy 38-year-old man in Massachusetts fell from his bed amid a violent seizure at 4 am. The commotion woke his wife, who found her husband on the floor, shaking and "speaking gibberish." He was rushed to Massachusetts General Hospital.

There, doctors witnessed the man have a two-minute-long tonic-clonic (grand mal) seizure, in which he lost consciousness and his muscles aggressively contracted. Doctors began the painstaking process of trying to piece together what was wrong by performing a battery of tests and interviewing his family.

By nearly every account, the man was in very good health. He had no history of seizures or of any cardiovascular, respiratory, gastrointestinal, genitourinary, or neurologic disorders. His toxicology screens were clear. He took no medications, prescribed or over-the-counter. He didn't smoke and rarely drank. There was no evidence that anything had happened to him recently that would provoke a seizure; the man had spent the previous day with his children, then he had dinner with his brother, who reported nothing out of the ordinary. The only initial hint of the diagnosis to come was that the man had immigrated to Boston from a rural area of Guatemala about 20 years earlier.

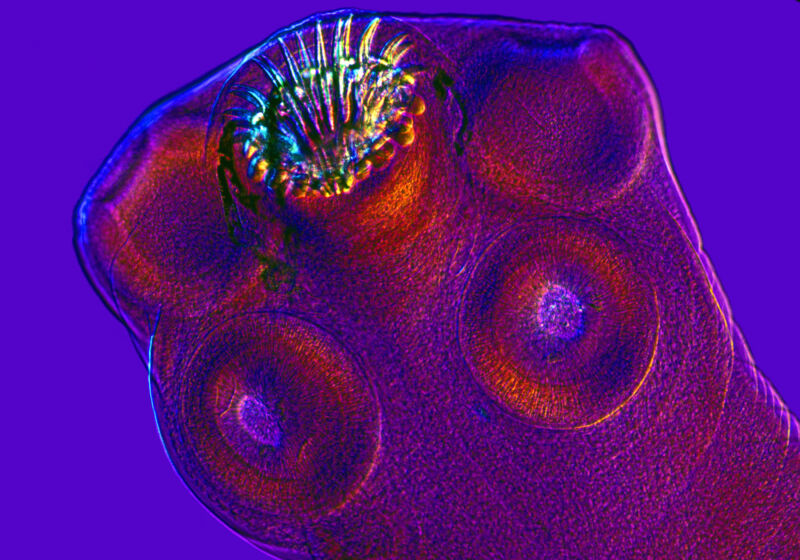

But when doctors performed a CT (computed tomography) scan of his head, they quickly narrowed the possibilities. The scan revealed three calcified lesions in his brain, and doctors homed in on the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis. In other words, larval cysts from a pork tapeworm had migrated to his head years ago and nestled into various parts of his brain. The doctors documented their work on the man's illness in a case study published on Thursday, November 11, in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Gut to brain

Learning about the path to neurocysticercosis is not for the weak of stomach; it's a cruddy calamity as nauseating as it is dangerous. The pork tapeworms, Taenia solium, typically tuck into human intestines, where they can grow to a shocking length of two to eight meters. The worm's victims, meanwhile, expel parasitic eggs in their feces. If that egg-laden excrement makes its way into an environment with pigs, the pigs can carry out the worm's life cycle by ingesting the eggs.

In the pig's stomach, gastric acid prompts the eggs to lose their protective coating and hatch into larval cysts, called oncospheres. These can penetrate the intestinal wall and take a ride through the pig's body via the circulatory system. They eventually burrow into the pig's muscles and lie in wait as cysticerci—which are typically not a bother for the pig.

But if a human ends up eating undercooked pork containing those larval cysts, the life cycle continues. In a human gastrointestinal tract, the worm emerges from its cystic form and sinks its hooks and four suckers into the human's upper intestines. There, it can happily slurp away for years, growing its ribbon-like body meters long and shedding more eggs. And the life cycle begins again.

Things go sideways, however, when a human—not a pig—ends up eating the worm's eggs. This can happen in a nauseating scenario in which someone infected with a tapeworm happens to have bad hygiene and also prepares food. In other words, a poopy-handed tapeworm victim contaminates a meal. In this case, the eggs hatch in the human's stomach, as they do in pigs. The larval cysts can end up in a human's muscles (cysticercosis), but they can also migrate to the eyes and brain (neurocysticercosis). This is a dead end for the worm and can develop into a big problem for the human.

Worms on the brain

In a human brain, the cyst goes through four stages. At first, it quietly lies in wait as a viable worm, provoking little to no immune responses—and thus no symptoms. This stage can last many years. But over time, the cyst degenerates and leaks fluid that alerts the immune system that a parasite is present, prompting a strong response. The cyst degenerates further and forms a nodule in the brain. Finally, the nodule becomes a calcified granuloma. Seizures have been associated with the inflammatory responses linked to the late-stage calcification.

Neurocysticercosis is the most common parasitic infection of the human brain and can cause headaches, confusion, balance problems, seizures, and even death. The disease is also the most common cause of acquired epilepsy. It's endemic in areas of Asia and Central America.

Given all of the medical information on the 38-year-old patient and his history of living in rural Guatemala, the doctors determined that neurocysticercosis was the most likely cause of his abrupt seizure and brain lesions.

After he was initially brought to the hospital, he was given multiple doses of an antiseizure medication, intubated, and transferred to the neurosciences intensive care unit. When he was stabilized and extubated, doctors began a treatment of two antiparasitic drugs and an anti-inflammatory drug, and they continued use of antiseizure medication. He was released from the hospital five days later with no remaining neurological symptoms or seizures.

Doctors followed up with him over the course of three years. Months after treatment, additional brain scans found that the swelling around the largest lesion in his right frontal lobe had gone down. He also remained seizure-free, though he was still taking his antiseizure medication. Because the calcified lesions will stay with him, it's unclear if or when he can stop taking the medication.

Comments

Post a Comment